I read Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Guns of the Dawn semi-recently. He’s an author I’ve wanted to check out for a while, and this book seemed like it would be right up my street. Austen-esque protagonist? I love Austen! Early modern setting? That’s my shtick! Military fiction? Was this novel written specifically for me!?!

Except, then I hated it. Not because of the story, which was meandering but not against my taste. (I can hardly call Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell an all-time favourite and then demand a tight plot.) Nor because of the characters, though they didn’t all hit for me. No, the thing that made me want to throw this book against the wall multiple times while reading it was entirely down to the setting.

Look, I don’t think fantasy ought to or even should follow history one-to-one. Even Guy Gavriel Kay is improved by his historical subversions. But your world needs to make sense and history can be a great guide in showing you how things were done and why. If you’re going to divert from that, first understand why things were done a certain way then ask yourself why and how they might be done differently in your world. Learn the rules before you break them, basically.

Near enough every part of the setting of Guns of the Dawn baffled and confused me both as a general reader but also someone with specific early modern historical knowledge. The things that stuck out the most were those related to the military aspects of the novel.

A lot of writers, especially fantasy writers, fall down when it comes to writing war. It’s very easy, as someone who hasn’t read enough on the topic, to accidentally imply or outright say something that makes absolutely no sense. In this novel, there were a few.

The scale, for example, made no sense. We’re told that every man aged something liked 15 to 65 has been conscripted, and now many of the women, from across this entire country. And yet the war is split into two fronts and one of them, admittedly the smaller but even so, only has a thousand combatants on one side. This implies a tiny population that is at odds with what we’re shown of this country throughout the rest of the novel. After all, a nation of only a million people would, with this level of conscription, have hundreds of thousands under arms. A thousand soldiers wouldn’t qualify as a ‘front’ in its own right.

Even the ability to raise that much of your population makes no sense. It implies a government with the ability to manufacture a huge amount of armaments, enough money to pay to keep that number of people under arms, and enough efficiency to organise it all. There’s a reason that level of mobilisation historically only came in the 20th century, after a huge expansion of the state bureaucracy and the invention of things like the telegraph, radio, and large factories for producing weapons. On the other hand, one of the 18th and 19th centuries’ largest mobilisations was the French ‘Levée en Masse’ during the French Revolutionary Wars. The levée conscripted all unmarried men between 18 and 25, a large number of them never showed up, and still it gave France an army larger than they knew what to do with given state capabilities of the time.

There’s of course the question of whether this style of society would ever conscript women. I don’t think they would, but that’s the one aspect I’m willing to overlook as it’s essential for the plot to work. Still, I would’ve liked to see the idea of conscripting women create more of a social debate, rather than everyone apparently just accepting it with a shrug of the shoulders.

The two fronts are also apparently close enough that artillery fired at one can be heard at the other. This implies the two sides are fighting over a reasonably small area, again at odds with the rest of the scale, but also making it unclear why these are even considered two separate fronts.

The style of warfare, where the two sides are bogged down and unable to make progress, looks like the First World War. But WW1 looked like it did because machine guns made defence more effective than offence. With the weapons the book depicts, there’s no reason the war should be a stalemate for so long. (Here I’m talking about the open fields of the primary front, not per se the swamp of the secondary one where terrain somewhat explains it.)

Speaking of which, why are the two sides fighting over the secondary front at all? It’s all swamps defended by a native population so, if one side moved through it, they’d be unable to maintain lines of communication back to their own side. Militarily, it’s basically impenetrable. Hence, there’s no need to defend or fight over it.

There’s also a strange lack of commissioned and non-commissioned officers. The more command and control in detail that needs to be exerted over a unit to make it effective, the greater a share of that unit will need to be COs and NCOs. A modern British infantry platoon of 30 soldiers has eight COs and NCOs. (About 25% of all soldiers.) During the age of linear warfare, this number was closer to about 10%. A British company, for example, would on paper have about 80 soldiers of whom 8 were COs and NCOs. How many COs and NCOs exist on this entire front? A single digit number, commanding almost a thousand soldiers. Around 1%, therefore. There’s just no way they could effectively command that number of soldiers.

Okay, so there’s all of that. But the thing that really, genuinely made me angry — the thing that showed an embarrassing and shocking lack of research into or interest in the historical period being borrowed from — was the rifles. Oh, the rifles.

So, please let me wax lyrical about rifles. What they are, what they were, and what they have never been. And then hopefully we can all learn something from Tchaikovsky’s mistakes.

What’s a Rifle?

A weapon with rifling. Okay, moving on.

Wait, no, but seriously though

Fine. Yes, a rifle is a weapon with rifling. In modern parlance it basically means any small-arm that isn’t a machine gun, shotgun, or sidearm, despite the fact that all of those weapons (except shotguns) do in fact have rifling. In the early modern period, however, before rifling was near universal, a rifle specifically meant a weapon that had rifling, as opposed to a smoothbore which did not.

So first, what’s rifling? For the uninitiated, rifling refers to spiral grooves along the bore of a weapon that engage the bullet as it travels down the barrel. They cause the bullet to follow their spiral pattern and thereby spin, meaning that the bullet will be spinning as it leaves the barrel. For physics reasons, this makes the bullet more accurate, reducing drop-off so the bullet travels straighter for longer.

Now, humanity has known that spinning things are more accurate for a fairly long time. For example, fletching on arrows and crossbow bolts was sometimes offset (as in, not pointing directly down the shaft but instead a little to one side) to cause the projectile to spin as it flew.

After the firearm was brought to Europe, it didn’t take too long for people to wonder how they could create the same effect for bullets. By 16th century, rifling was invented and being added to firearms. But it wasn’t common. Why?

Well, rifling came with a couple of large downsides. First, as these weapons were being handmade, it made them more time consuming and expensive to produce. Second, they were more difficult to maintain. But the big problem was the bullets.

You see, for rifling to be effective, the bullet has to be the same size as the bore, so that the rifling is actually in contact with the bullet. That’s hopefully obvious. But it wasn’t how most firearms worked at the time. Remember, at this time bullets had to go in the same way they came out. So, you put them in the barrel them pushed them to the end with a ramrod. By making bullets slightly smaller than the size of the bore, they were easier to push down.

But a rifle needed a bullet exactly the same size as the bore, otherwise what was the point? This creates two problems. One, you need to be much more accurate in your bullet production. At the time, bullets were produced by putting lead in a round mold and bashing it into shape. You can imagine the difficulty.

And then two, it’s just much harder to push that bullet down the barrel. Rifle users reportedly often had to carry mallets to smack the end of their ramrod and thereby force the bullet down. The added time of pushing this bullet down the barrel made rifles much, much slower to reload.

So, rifles were harder to produce, harder to maintain, harder to supply, and much slower to fire. For all that, you got an advantage to accuracy. As a trade off, it wasn’t worth it. In the period of linear warfare, battalions of hundreds of soldiers would face off against other battalions at ranges of a couple hundred meters at most, firing volleys that didn’t have to hit a specific soldier, just the vague mass of enemy soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder. (To reiterate, your target usually wasn’t a man, it was a unit one-man high, two-to-three men deep, and scores-to-hundreds of men wide.) In that context, rate of fire counted for much more than accuracy of fire. So, in the 16th, 17th, and most of the 18th centuries, rifles were civilian weapons for self-defence and hunting, but they were not adopted by militaries.

This began to change in the back half of the 18th century. North America, with its rugged terrain and mass of forests, favoured a greater level of skirmishing when compared to Europe, which had long ago been largely deforested. So, in the French and Indian War and American War of Independence, small units of civilian militia armed with their own rifles proved that there was military utility to be found in the weapons. They could harass enemy units at ranges that kept them safe from return fire, then run away when the enemy moved up. They could take aim at specific soldiers, allowing officers to be targeted to disrupt enemy command and control. You still wouldn’t want everyone to use them, but specialist units proved useful.

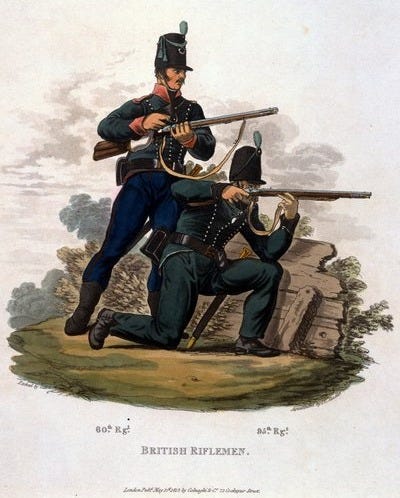

With these experiences in mind, the British debuted their own skirmish-focused rifle-armed soldiers: the 60th (Royal American) Regiment and the 95th (Rifle) Regiment. Yet still, the rifle did not and could not take off as a general service weapon. Rifle armed skirmish troops were useful in assisting regular line infantry, but could not replace them, and would not until someone solved the reloading issue.

Finally, in the 1840s, someone solved the reloading issue. The Minie ball, named after its inventor Claude-Étienne Minié, completely changed what a bullet was. Instead of being spherical, it was shaped like a shuttlecock, with a skirt at the back. It had to be loaded in the correct orientation but, assuming you did that, the force of the blast propelling the bullet forward would also flair the skirt out. This allowed it to be slightly smaller than the bore on the way in, but then to grow to the size of the bore, engaging the rifling, on the way out. Brilliant.

With reloading now faster than ever, many European militaries quickly switched to rifles as their standard weapon. Minie ball rifles would go on to be the mainstay in conflicts such as the Crimean War and American Civil War, before being replaced towards the end of the century when breach-loading weapons (i.e. those that load directly into the working parts rather than having to go down the barrel) were mass adopted.1

What Guns of the Dawn got Wrong

So, to return to our case study of Guns of the Dawn, now with the knowledge of rifles and their history, what did it do that was so offensively awful?

The nation we’re following uses smoothbores but our main character quickly realises that the enemy’s weapons are more accurate than theirs. My thought at this point was along the lines of I hope that’s not rifles because it doesn’t make sense that no-one would know about them yet.

Then she goes to her commanding officer, who assures her that they’ve deconstructed captured enemy weapons and, nope, there’s nothing different about them. Okay, not rifles then — probably something magic. Anyway, I thought, if they were pre-minie ball rifles, they’d be noticeably slower to fire.

As the book went on, I got a sinking feeling in my stomach. I became more and more convinced that, despite it not making sense, these superweapons were in fact rifles. Finally, it was confirmed.

The enemy commander tells the main character what they are. Even explains what rifling is and tells the main character that her country’s engineers will understand the explanation.2 We learn that the main front has collapsed and, later, are told that the reason for that is the rifles. They were just too accurate: they broke a frontal cavalry charge and the infantry that moved up to support that charge.

Wait, What!?!

So this doesn’t work on any level.

First, as I said earlier, it makes no sense that rifles would be a new invention to this 19th century inspired world. Unless you’ve got a compelling explanation (which is not provided) I just cannot comprehend how a society could discover the steam engine before the concept of ‘spinning makes accurate’ and ‘grooves on musket makes spin’, given we historically discovered the latter centuries before the former. Steam engines in particular imply so much technological development that the lack of knowledge of rifling becomes ludicrous, like if someone knew linear algebra but not long division.

Next, rifling is immediately obvious once you’ve seen it. These aren’t unnoticeable grooves: pistol duels would start with the seconds (those who assisted the duelists) inspecting the pieces for rifling. They would sometimes miss it, but that still shows that rifling can be seen with the naked eye even without taking the weapon apart. If you do take it apart, you really can’t miss it. Even if you personally can’t work out what it does, it’s clear that there’s something there and therefore ridiculous that this army did that and concluded that there was nothing different about the enemy weapons. Did they never even send it back to a weapon-smith or military engineer for inspection? These people are too stupid to live.

Most importantly, mass adoption of rifles before the invention of the minie ball (which isn’t mentioned in the book) would be a disadvantage to an army! Maybe not in the swamps of the secondary front, but certainly on the open fields of the primary front. Yet, it’s on that front that the enemy broke through purely due to their use of rifles. Take that frontal cavalry charge that failed against the enemy rifles. Historically, that’s not how that went down. Famously, when French cavalry charged the British 95th Rifles at the Battle of Waterloo, the 95th ran back and took cover in infantry squares. That cavalry charge failed because they couldn’t break through the wall of bayonets they suddenly found themselves in front of, not because rifles cut them down before they could close the distance.

So, none of this makes sense. But the worst thing, the very worst thing, is that if Tchaikovsky had done his research there was a blindingly obvious solution. What was invented after the steam engine and made rifles a viable standard issue weapon? The minie ball!

Here’s how a better version of this novel plays out:

Our characters notice that the enemy have very accurate weapons but can’t make sense of it. If they’re rifles, why can they maintain such a rate of fire? They capture one of these rifles take it apart and, sure enough, it's a rifle. How have they gotten a rifle to fire so quickly? The commanding officer, disbelieving, assumes that they’re using mostly smoothbores with a few rifles mixed in, and the soldiers are making a lot of fuss over nothing.

Maybe when she’s captured, the main character sees these strange bullets and tries to describe them back at camp. Initially no-one understands and some wonder if what she’s describing were bullets at all. Finally, it gets explained what these are and how they work.

Besides now actually making sense, this would also fit in better with the technology shown in the novel, which is after the steam train but before the telegraph. Indeed, the more I thought about it, the more it seemed baffling that this wasn’t the case.

For example, that failed cavalry charge on the primary front I keep harping on about. It’s described very reminiscently of the Charge of the Light Brigade, an event seared into British cultural memory thanks to Tennyson’s poem and which happened during the Crimean War. The Crimean War was also the first major war to use the minie ball, where British and French troops reported mowing down Russian soldiers who were still using smoothbores — just like happens in the book.

Part of me even wonders if Tchaikovsky initially used the minie ball but was asked to change it as a general audience might not understand. That could explain why the term ‘rifle’ slipped through before the concept was explained to our main character. But, if that’s the case, then I’m even more mad at Tchaikovsky for sacrificing good worldbuilding to dumb down his book. And, anyway, I don’t really believe this: the rest of the worldbuilding is equally shoddy, after all.

Lessons Learnt

I hope the big takeaway from this can be that, through research and better worldbuilding, we don’t have to sacrifice story. In fact, quite the opposite. That same story of a wonder-weapon, the thematic idea that innovation and bureaucracy are what really win wars, rather than courage and the physical ability of soldiers, would be better told by hueing closer to the history and to what makes sense.

So lets do our research, think through our implications, and tell better stories because of it. About rifles, sure, but about everything else too.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this piece, feel more than welcome to like, comment, or subscribe. If you didn’t, likewise.

And if you would like to see me put my money where my mouth is, check out my short fiction. Here’s a great place to start if you want to see my attempt at early modern military fiction done right:

Though the Prussians and some others had been using an early breach-loader, the needle gun, instead of switching to a minie ball rifle. The prioritisation of reload-speed over accuracy was vindicated during the Franco-Prussian War, perhaps the only true example of a war being won by a wonder-weapon which further showed why accuracy was not the primary concern during that era.

Adding insult to injury, the book (my copy, at least) actually uses the term ‘rifle’ to refer to the smoothbore weapons of our protagonists just before it’s explained what rifles are. So, the term is used for weapons that aren’t rifles, before the main character could even use that term. This is presumably a line-editing mistake, but felt indicative of the lazy worldbuilding.

Good points! The idea of rifling is ancient, I believe the first illustration of it is from Leonardo Da Vinci. But one problem with your alternative storyline: Wouldn't they discover the enemy are using weird balls when they are extracting them from their own men the infirmary?

I enjoyed this article! I too am bothered by nonsensical depictions in writing and other media, especially in military and history matters - this frequently annoys my wife!

Machine guns played some role in creating the stalemate on the Western front. I think a larger contributor, though, was artillery advancements (which were the primary cause of trench digging), as well as something else you mentioned - new methods of mass conscription and the stress it put on stronger but still not sufficient logistics systems. Continent-sized armies were able to absorb massive losses without being beaten but also lacked the organization to penetrate into hostile territory then hold it.

The stalemate was unique to the Western front and was ended in part by the USA joining and building a massive rail system and engaging in maneuver warfare. Tanks also gave commanders, especially UK commanders, new avenues of assault that artillery used to suppress with ease, adding a chaos factor to formerly stable lines.

Machine guns, and other continuously advancing infantry weapons past that area (shoulder launched rockets, fpv drones) are capable of incredible destruction. But paradoxically these technologies still inflict the smallest portion of casualties - artillery is still king, with them inflicting 75-90% of battlefield casualties in wars. Infantry's main role, including machineguns, is still mostly suppression of the enemy and being a layer in the complex "onion of defense" at the center is which is a battery of big long range guns

If someone had brought more trench axes and wwi-era strategy to the US Civil war, and nothing else changed, i think it possible that war would have never ended, or possibly lasted twice as long.